I've been intrigued by boxwood shrubs for

over a quarter century now, especially the older varieties found here and there in front yards and gardens around Victoria. Often they appear as thick-set hedges or path edgings, less frequently as screen plantings or specimen shrubs. To me the mere presence of boxwood around an older house suggests age and settled living, making it feel more homey. Years after first noticing these older plantings, I learned how to transfer them (and by extension, hints of their eras) in the form of cloned offspring, a trick leading to a second life in a new locale. While I

know little

technically about them, the older varieties strike

me as having leaf textures, colour variations, and growth habits

that differ subtly from today's popular offerings. Some are decidedly coarser in appearance than current more-refined types while a

few are delightfully variegated and come with a slight roll to their leaves.

I first began noticing these relic boxwood on walks taken in older Victoria neighbourhoods, where they firmly anchor houses to their surroundings even in smaller front yards. Most often they appear as fairly coarse hedging, tracing the line where lot meets sidewalk and marking a rectangular edge to the domestic realm while framing an access to the front door. Here they may lend hints of architectural intent to otherwise utilitarian front paths and retaining walls, typically made of concrete. Less frequently, they are found serving as specimen shrubs in a border or foundation planting, where they are also likely to be taller and rather more open in

appearance. In our rural suburbs, where lots tend to be larger and sidewalks more rare, box hedging often echoes the property's frontage without defining it sharply. In these situations they serve as screens helping to integrate native species and natural features with human landscape choices and are often presented in the looser manner suited to more rural surroundings.

Boxwood are also found tracing the outline of front paths to graphic effect, adding visual interest and vertical dimension to the ground plane. Somehow their mere presence intensifies feelings of long-habitation around older homes, while adding form and character to their access spaces. Sometimes these front or side yard hedge plantings comprise most or even all of the small garden.

This association of long-habitation with the presence of boxwood plantings likely derives from the fact humans have grown them ornamentally for so long and across many different cultures, both in the West (from before the Romans) and in the East in Korea, China and Japan, where they are prized for their low mounding forms. Boxwood are native to many areas of the globe and have been used to order human landscapes for so long now that they are thought of as the world's oldest ornamental plant. Hence boxwood's presence imparts a sense of age no matter how recent the planting may be.

Ornamental use of boxwood today is broadly consistent with what we know from written records about prior use, most notably by wealthy Romans at country villas in the heyday of empire. Here it served as garden hedging and as edging for paths, and as gradations between garden levels, and for topiary too - but placed and arranged without any great formality. "The literary mentions of box clearly depict the plant's use in high-status ornamental gardens in Italy. Pliny describes in detail how to take cuttings of box for topiary bushes and Pliny the Younger's description of his own garden layout had box hedges separating paths. In fact, the selection of box as an ornamental garden plant has been attributed largely to its suitability for topiary." (L.A. Lodwick, Evergreen Plants in Roman Britain).

Boxwood are broad-leafed evergreen shrubs with a naturally compact appearance, so their shape remains stable over the course of the seasons. Part of the charm of these slow-growing plants is how readily they take to the shears, responding with architectural definition for year-round garden structure. The more-dwarf varieties can be set out as low geometric shapes, or in lines, or treated as incidents, elaborating structure in a garden with a note of elegance. The taller and ultimately tree-forming varieties work well as screens or as specimen shrubs whose upward growth can be held in check with regular pruning. Lodwick also notes that box "obscures temporal changes between the seasons", making them attractive to gardeners seeking year-round effects. Boxwood can provide welcome continuity in gardens whose scenic show of flowering plants disappears entirely from late fall through early spring.

Use of boxwood by wealthy villa owners declined with the demise of the Roman empire, but little is known about ornamental use in the ensuing long period of instability and warfare. With the return of peace and rising wealth in the later middle ages, the old habit of edging beds and paths in clipped boxwood revived among prosperous Italians. This easily shaped shrub appears to have an affinity for marking bounds and edges in the hands of ornamental gardeners, a quality this era would take to extremes. Geometry was in fashion then too, and in aristocratic gardens this resulted in heightened formality, symmetry, and a much-stiffened use of dwarf boxwood. From Italy, a fad for these stiff designs spread across all of Europe, ultimately giving rise to rigid parterres in Holland and France (as at Versailles, for example). This trend towards an unrelenting confinement of plant growth was meant to symbolize wealth, grandeur and social standing, as it takes vast labour to constrain boxwood in the despotic manner pictured below.

European aristocrats, deploying fleets of gardeners, turned shaped boxwood into symbols of pomp and splendour in their gardens, while demonstrating man's growing control over nature. Even remote Norway, with a climate inhospitable to box cultivation except for a narrow strip along the southwest coast, adopted this stiffened look. Apparently, Norwegian gardeners working on grand gardens elsewhere brought rooted cuttings back home, setting these out parterre-style at the manorial homes of rich merchants. Interestingly, in Norway the vogue for tightly clipped plantings steadily gave way to a loosened style of arranging and trimming boxwood, a trajectory continuing today (see photo cluster, below right). English gardeners in the seventeenth century were also using boxwood in stiffened knots, mazes and parterres, but topiary uses had long been popular there. Topiary includes both representational shapes (birds, animals, initials, heraldry) and architectural or geometric shapes (pyramids, squares, globes, eggs). Despite the national inclination to trim box into fantastic shapes or set it out in parterres and knots, English garden use was never as stiff as that pioneered in France, Holland and Italy, and the counter tendency towards more-relaxed arrangements always had a following. Later, when gardening became a more middle-class pursuit and the cottage-garden style came into fashion among owner-designers, the less-formal use of boxwood spread even more widely through English gardens.

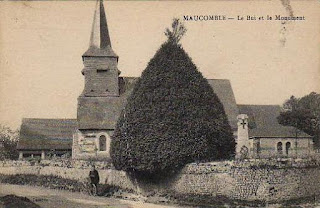

The long human association with boxwood across Europe is due in part to its widespread presence as a native species, the tree version of it providing a hardwood valued for certain specialized articles like fine boxes, combs, carved religious beads and musical instruments. Pagan forebears also used boxwood branches over the ages in their rites and rituals, prizing them for the plant's year-round greenery and longevity. The ancient Gauls regarded their long-lived native boxwood tree as a symbol of immortality. In more recent times these trees have sometimes been allowed to reach great size within settlements (shaped for a degree of compactness, as above). The relic boxwood pictured in the churchyard here has become a mature tree reckoned to be between 500 and 700 years of age.

The fashion for boxwood bones in garden design was reinforced among prosperous landowners across the entire western world during the seventeenth century, a time of colonial expansion and rising mercantile wealth. Boxwood reached America too in this era, where it was valued as a potent reminder of the home landscape and as a tangible symbol of continuity with life there.

The fashion for boxwood bones in garden design was reinforced among prosperous landowners across the entire western world during the seventeenth century, a time of colonial expansion and rising mercantile wealth. Boxwood reached America too in this era, where it was valued as a potent reminder of the home landscape and as a tangible symbol of continuity with life there.

Early American colonists brought slips and roots of boxwood with them to adorn homesteads in the new land. The plant had long been emblematic of 'home', a value it still carries. In the southern colonies especially, where extensive plantation gardens were usually maintained by African American slaves, boxwood readily gave novel form to new-world garden design. George Washington, America's first President, used boxwood extensively to frame gardens at his Mount Vernon estate, and Thomas Jefferson in turn rooted cuttings from Washington's gardens for his estate at Monticello. From early on an American love affair with these shapely, reliable plants has flowed and ebbed repeatedly, dividing allegiance between the stiff look of formality and something informal and more relaxed (and likely better suited to garden making in previously untamed nature). The 1892 house by San Francisco architect Willis Polk standing on Russian Hill (above right) has a foreground planting of boxwood used informally. The descent of Lombard Street (above left) is structured by switchbacks edged in trimmed but flowing dwarf boxwood.

The fashion for boxwood bones in garden design was reinforced among prosperous landowners across the entire western world during the seventeenth century, a time of colonial expansion and rising mercantile wealth. Boxwood reached America too in this era, where it was valued as a potent reminder of the home landscape and as a tangible symbol of continuity with life there.

The fashion for boxwood bones in garden design was reinforced among prosperous landowners across the entire western world during the seventeenth century, a time of colonial expansion and rising mercantile wealth. Boxwood reached America too in this era, where it was valued as a potent reminder of the home landscape and as a tangible symbol of continuity with life there. Early American colonists brought slips and roots of boxwood with them to adorn homesteads in the new land. The plant had long been emblematic of 'home', a value it still carries. In the southern colonies especially, where extensive plantation gardens were usually maintained by African American slaves, boxwood readily gave novel form to new-world garden design. George Washington, America's first President, used boxwood extensively to frame gardens at his Mount Vernon estate, and Thomas Jefferson in turn rooted cuttings from Washington's gardens for his estate at Monticello. From early on an American love affair with these shapely, reliable plants has flowed and ebbed repeatedly, dividing allegiance between the stiff look of formality and something informal and more relaxed (and likely better suited to garden making in previously untamed nature). The 1892 house by San Francisco architect Willis Polk standing on Russian Hill (above right) has a foreground planting of boxwood used informally. The descent of Lombard Street (above left) is structured by switchbacks edged in trimmed but flowing dwarf boxwood.

The use of boxwood in older Victoria gardens

is a more recent and far less-self-conscious matter than

the stiff look of formal parterres, town settlement here

only having come about in the latter half of the nineteenth century. From the turn of the twentieth century and with Victoria becoming a small city, boxwood

have regularly been used in local shrubbery gardens, typically as front or side yard hedging that is kept with a certain roughness of texture. My impressions of this versatile plant grew from noticing one such hedge crowning a low granite wall, first seen back in 1988 at the house at Fort and Linden pictured below.

This hedge, which seemed venerable to me thirty years ago, has a timeless quality that accompanies the genre. Once aware of the dynamic relationship between boxwood and stone walls, I began to notice it more and more, and

of course I coveted the specific effect for the home garden.

This hedge, which seemed venerable to me thirty years ago, has a timeless quality that accompanies the genre. Once aware of the dynamic relationship between boxwood and stone walls, I began to notice it more and more, and

of course I coveted the specific effect for the home garden.

This hedge, which seemed venerable to me thirty years ago, has a timeless quality that accompanies the genre. Once aware of the dynamic relationship between boxwood and stone walls, I began to notice it more and more, and

of course I coveted the specific effect for the home garden.

This hedge, which seemed venerable to me thirty years ago, has a timeless quality that accompanies the genre. Once aware of the dynamic relationship between boxwood and stone walls, I began to notice it more and more, and

of course I coveted the specific effect for the home garden.

At some point in the early nineties I happened to notice an older boxwood hidden behind the fence separating our yard from the neighbour's, which is a panhandle lot subdivided from the original grounds. I realized at that point that our home garden had at one time

hosted boxwood – or, at the very least, a single specimen - and I immediately wanted to reintroduce it.

This old plant was still lovely in form, semi-shaggy after years of minimal upkeep, and with a distinct tilt to its growing habit. Strangely though, not long afterwards my neighbour elected to rip it out, then offered it to me with its rootball badly mangled. I took it of course, then haplessly attempted a rescue by replanting it in a shady spot and keeping it watered. I doubted its chances of survival,

especially coming into summer's heat, and so was not surprised when it quickly expired.

especially coming into summer's heat, and so was not surprised when it quickly expired.

But I wasn't at all pleased with how this went down, realizing later that I had missed the opportunity to take cuttings from the doomed plant. I suspect I've been making up for that failure ever since! In fact I was only just learning to root cuttings, so lacked the awareness to prompt the thought. However, once the feasibility of this process became clear, I realized it could easily be applied to any older boxwood that happened to catch my eye.

Some years after the mangling incident, another situation inviting relic box rescue arose, and by then I was ready for it. I happened to be working with the Provincial Capital Commission (PCC) in the mid-1990s, while it oversaw restoration of St. Ann's Academy and the renewal of its extensive grounds. St. Ann's is one of those regional institutions with a long history of mixing boxwood plantings into its surroundings. Today boxwood deftly extend a sense of architectural arrangement outwards from the building's vertical lines to the park-like setting pictured below, here aided and abetted by yew, holly and hydrangea, which are also regionally significant landscape plants.

One day, while touring the grounds with PCC staff, I noticed a trio of shaggy older boxwood hiding in a rarely visited corner at the northwest end of the arboretum. Evidently these mature plants had been overlooked for some time in their overgrown shrubbery. I found them fetching, reminiscent of the deceased home boxwood, and so decided to try cloning them for our own garden. There was some urgency to this rescue, as a plan to open a new public access at the corner of Humboldt and Blanshard made it unlikely these oldsters would survive the construction (and they did not). So with permission from the PCC, I returned and took several dozen growing tips for rooting. I planted these directly into garden soil in a shaded spot and kept them well-watered, hoping for the best. I was excited to attempt preservation of this token of local garden history, for incorporation one day into our home garden. And this first try at multiplying relic boxwood was ultimately to have beneficial consequences for design I did not remotely anticipate at the time.

It took about a year of keeping the

cuttings moist until they developed roots strong enough to support new

growth. I lifted these a year later, transferring them into pots where they grew on happily for many years. As a result, we began playing around with potted boxwood as garden accents, increasingly using them to add visual interest or soften transitions between spaces. With adequate watering and occasional light feeding, boxwood tolerate pot culture in our climate extremely well.

Eventually the rooted cuttings reached a size where planting them out suggested itself. At this point I made the fateful choice to set the St. Ann's boxwood out in curving lines (above). This we did in a number of places in proximity to stone retaining walls or other stone features, in order to gain synergy of effect.

Eventually the rooted cuttings reached a size where planting them out suggested itself. At this point I made the fateful choice to set the St. Ann's boxwood out in curving lines (above). This we did in a number of places in proximity to stone retaining walls or other stone features, in order to gain synergy of effect.

I was surprised how readily

these gentle boxwood curves made themselves central to the

garden's personality and overall look, so much so that it would be hard to

imagine it without their presence now. Many years on they continue

to provide year-round structure while greatly enhancing the mood of age and repose in our woodland garden setting. The success of this foray in boxwood propagation, leading eventually to entirely new planting possibilities, only whetted my appetite for more of these relics. I see this practice as

enabling the transfer of some mood and magic from one old garden to

another, a clear romanticization of the past. No matter, it remains an excellent way to gain fresh plant material that ultimately contributes to intensifying feelings of serenity and repose in a garden.

The older institutional settings that dot our urban region are among the more likely places to encounter large collections of relic boxwood, where they are sometimes used with greater formality than around homes. These boxwood may be trimmed up into neat rectangular hedges marking the edges of beds or perimeters, grown as specimens to a greater and more natural

shape, or used as screens manifesting a certain

residual shagginess. Boxwood can add significant texture to any garden or landscape setting and will, varying with closeness of clipping, handily fill in a given shape.

Hatley Castle's grounds in Colwood sport a major collection of boxwood from different eras, some of which are said to be over a hundred years old. Built in 1908 by Samuel Maclure for James Dunsmuir, heir to the Vancouver Island coal family's fortune, Hatley's immediate surroundings include a captivating Italianate garden that uses boxwood for bed edgings. Overall, Hatley Castle's mix of formal and informal elements effectively binds house, gardens and grounds into a unified whole - a place that feels like its parts all belong together. This is based on using boxwood extensively to define intermediate spaces as outdoor rooms between the house and its surrounding woodlands. Hatley Castle is unique in the variety of boxwood used in contrasting styles of presentation, from orderly formal parterres and knots to sophisticated architectural sequences on terraces or as grand mounds and point plantings punctuating walkways.

The six shots beside and above illustrate mounds and chopped pyramids in pots along walks, boxwood edgings in the Italianate garden (said to date from the 1930s), boxwood in a parterre of circular shapes at the front entry that are of more recent vintage, and rows of older box used as screens, which may date from the earliest days of the building.

shape, or used as screens manifesting a certain

residual shagginess. Boxwood can add significant texture to any garden or landscape setting and will, varying with closeness of clipping, handily fill in a given shape.

Hatley Castle's grounds in Colwood sport a major collection of boxwood from different eras, some of which are said to be over a hundred years old. Built in 1908 by Samuel Maclure for James Dunsmuir, heir to the Vancouver Island coal family's fortune, Hatley's immediate surroundings include a captivating Italianate garden that uses boxwood for bed edgings. Overall, Hatley Castle's mix of formal and informal elements effectively binds house, gardens and grounds into a unified whole - a place that feels like its parts all belong together. This is based on using boxwood extensively to define intermediate spaces as outdoor rooms between the house and its surrounding woodlands. Hatley Castle is unique in the variety of boxwood used in contrasting styles of presentation, from orderly formal parterres and knots to sophisticated architectural sequences on terraces or as grand mounds and point plantings punctuating walkways.

The six shots beside and above illustrate mounds and chopped pyramids in pots along walks, boxwood edgings in the Italianate garden (said to date from the 1930s), boxwood in a parterre of circular shapes at the front entry that are of more recent vintage, and rows of older box used as screens, which may date from the earliest days of the building.

Another trove of these relic boxwood is found at Camosun College's Lansdowne

Campus, where lines of box hedging frame the perimeter on two sides of the extensive grounds. These long runs of hedging colour up dramatically with the seasons, showing as fresh greens throughout our long spring while turning an eye-catching orangey-gold in fall and winter. This campus also has an intriguing raised circular parterre of clipped yew and

boxwood that echoes the classical symmetry of the Young building, as well as specimen plantings that have

been allowed to grow into larger mounding sentinels. Finally, there are many old boxwood, some hard-clipped and maintained, others badly overgrown and calling for attention, around the Dunlop mansion (Maclure, 1928) which forms an integral part of the landscaped grounds on this lovely part of the campus.

been allowed to grow into larger mounding sentinels. Finally, there are many old boxwood, some hard-clipped and maintained, others badly overgrown and calling for attention, around the Dunlop mansion (Maclure, 1928) which forms an integral part of the landscaped grounds on this lovely part of the campus.

Another collection of relic boxwood survives on the grounds of the BC Legislature, where a further adventure in plant-transfer was to occur. One day, as a new-minted MLA, I was interviewed in the Rose Garden, a small sunken terrace on the

west side of the legislature with a broken circle edged in old box (below).

It happened these hedges were being pruned that very day,

so it was evident exactly how much of their growing tips were to come off. There seemed to be just enough length to take viable cuttings, so I had a word with the gardener before taking a handful from above the trimmed height. I then carried on with the usual process of rooting them in pots.

This approach is slow and improvised compared to the ease and certainty of greenhouse propagation, yet it succeeds regularly here in our temperate marine climate. So it happened that by the time my term of office was up, the newbies were nearly ready to be planted out.

I decided to place them at the front of our house, along the edge of a stone retaining wall where I felt they would show well. The layout ran along the edge of our parking spot, making a hard right turn for the steps up from it (so requiring an l-shaped planting). I took a playful approach to the challenge and wound up with an unconventional layout. The result, more modernist than traditional, uses boxwood in units or short runs rotated slightly across the centreline of the l (below right). I further complicated matters by introducing a second type of relic boxwood, with a more rounded shape, to punctuate the runs of squared-up box at various points. This complexity has given it a rather funky, segmented quality overall. The plants have adapted well to their difficult growing site, and the design seems to hang together reasonably well despite its unusual qualities.

This approach is slow and improvised compared to the ease and certainty of greenhouse propagation, yet it succeeds regularly here in our temperate marine climate. So it happened that by the time my term of office was up, the newbies were nearly ready to be planted out.

I decided to place them at the front of our house, along the edge of a stone retaining wall where I felt they would show well. The layout ran along the edge of our parking spot, making a hard right turn for the steps up from it (so requiring an l-shaped planting). I took a playful approach to the challenge and wound up with an unconventional layout. The result, more modernist than traditional, uses boxwood in units or short runs rotated slightly across the centreline of the l (below right). I further complicated matters by introducing a second type of relic boxwood, with a more rounded shape, to punctuate the runs of squared-up box at various points. This complexity has given it a rather funky, segmented quality overall. The plants have adapted well to their difficult growing site, and the design seems to hang together reasonably well despite its unusual qualities.

This habit of collecting older boxwood isn't abating despite the spatial limitations of our suburban lot. It turns out that many different types have been used here over the past century, so new discoveries of older boxwood are still being made. I find they tend to be less glossy, often duller in colour, and coarser and bulkier in habit than today's neater offerings. Perhaps more of the older box are in fact 'sempervivens' (native species, so given to taller growth) while the newer ones have tended to be 'suffruticosa' (dwarf English variants that are naturally mounding and of tighter foliage density)? However that may be, my main interest is to obtain more of the look and feel of prior use by transferring older examples into our home garden.

Boxwood make an attractive choice of garden shrub insofar as they have few special requirements in our climate and soils. While they are said to thrive in full sun, they seem to prefer sites where they get some relief from direct light for part of the day. It may be that on upland sites like ours boxwood flourish better without full exposure. Some varieties will tolerate deeper shade too, but many tend to be more straggly in such settings. It's vital to water them during our prolonged annual drought (last year over three months with no substantial rain!) but not too much. They like soil that drains well and will not put up with wet feet. There is no need to amend most soils for boxwood (heavy clay excepted) beyond top dressing with leaf compost and possibly mulching (but don't mound either up to the leaf line, as that enables the diseases box is susceptible to). Also on the plus side, their slightly pungent odor and likely bitter taste deter deer from browsing, a blessing for gardeners facing spiking herds. One caution here: male deer growing new antlers resort to thick shrubs as rubbing points, so any coarser boxwood along a buck's regular path is liable to serious damage. A further plus, to this point at least, is that Victoria's arid summers seem protective against the boxwood blight afflicting moister, more humid climates. There are other diseases that may develop from over-pruning, over-fertilizing and over-watering, but the likelihood is remote if one avoids these practices. However, this may all change in the future, as a rapidly changing climate rearranges what plants can flourish here (just look at the amount of die-back in our cedars).

With well-rooted cuttings in hand, the gardener faces choices of form for planting out, coupled with degrees of looseness in trimming. Are they to be grown as specimen plants or as part of a shrubbery, shaped

into balls, pyramids or squares, or grouped to run in gently curving or staggered lines? Are they to be left to elaborate their natural billowing form, clipped more closely to emphasize their mounding quality, or rendered into some more fantastical shape via the legerdemain of pruning? Working through these choices is what designing your garden with boxwood is all about. I enjoy using them playfully and without too much preconception, as they can show well in pretty much any form they are given or allowed to take. If you have boxwood as individual specimens in pots, you can use them to try a layout on for fit. A playful approach keeps it

interesting for the amateur gardener, who is free to revel in having a supply of

plants and just follow inclinations in placing them. Boxwood do not have to be used in a formal way, and in fact there is a strong case that a more informal and relaxed look better aligns with the natural landscape we inhabit. In the end, as with everything in a garden, one is looking for mixture in an interesting balance.

If you're of a mind to try rooting

relic boxwood here in Victoria, you won't need much equipment to get started

(other than a pair of secateurs and approval to take cuttings). If there's any delay before the cuttings go into the ground, you need to ensure they remain hydrated. Box roots quite easily

given decent conditions, which in our relatively benign climate can be out of doors. (In places with harsher winters, a greenhouse may be needed for rooting cuttings, and the range of cultivars severely limited by the need for hardiness to counter prolonged freezing). Here on the peninsula at the southern tip of Vancouver Island, with weather moderated by proximity to the ocean, the range of usable cultivars is broad and the approach to rooting is wide open. However, be aware that sudden reversion to frigid winter can subject unrooted slips to frost heave, which projects them right out of the soil and means resettling them afterwards. I think it is best to take cuttings in the fall when the rains are returning, so that plants lacking roots aren't subject to the added stress of sustained drought. I always select cuttings of vigorous young growth (avoiding older, harder wood), strip off most of the leaves to expose

If you're of a mind to try rooting

relic boxwood here in Victoria, you won't need much equipment to get started

(other than a pair of secateurs and approval to take cuttings). If there's any delay before the cuttings go into the ground, you need to ensure they remain hydrated. Box roots quite easily

given decent conditions, which in our relatively benign climate can be out of doors. (In places with harsher winters, a greenhouse may be needed for rooting cuttings, and the range of cultivars severely limited by the need for hardiness to counter prolonged freezing). Here on the peninsula at the southern tip of Vancouver Island, with weather moderated by proximity to the ocean, the range of usable cultivars is broad and the approach to rooting is wide open. However, be aware that sudden reversion to frigid winter can subject unrooted slips to frost heave, which projects them right out of the soil and means resettling them afterwards. I think it is best to take cuttings in the fall when the rains are returning, so that plants lacking roots aren't subject to the added stress of sustained drought. I always select cuttings of vigorous young growth (avoiding older, harder wood), strip off most of the leaves to expose the stems for rooting, use a hormonal rooting compound (#2

is likely best for a shrub like box) to encourage root growth, and employ ordinary garden soil as a

medium, amended with a little leaf compost if it is available. I like to put the cuttings straight into

pots, keeping them out of direct sun (dappled shade works

well), and ensuring they remain moist (they initially absorb moisture through

their stems, so pots can dry out very quickly).

After a year or so, you will see signs of fresh growth and then it's

either pot them on or plant them out.

the stems for rooting, use a hormonal rooting compound (#2

is likely best for a shrub like box) to encourage root growth, and employ ordinary garden soil as a

medium, amended with a little leaf compost if it is available. I like to put the cuttings straight into

pots, keeping them out of direct sun (dappled shade works

well), and ensuring they remain moist (they initially absorb moisture through

their stems, so pots can dry out very quickly).

After a year or so, you will see signs of fresh growth and then it's

either pot them on or plant them out.Down the road, I can see myself introducing a screen of antique boxwood at the front of the house where it will help to mask noise and movement on a busy street. Likely this will be left to develop a bit more openly than city hedging. Loosened treatment allows box to develop its bulk more in line with natural growth, yet clipped enough to render its shape intentional. Our garden seems ideal for this looser use, being in a piece of woodsy suburbia with many native oaks. As an overall direction for garden design with boxwood, I find the following comments from the American Boxwood Society to be useful:

"Generally speaking the landscape architect...errs in stressing formal effect, whilst the amateurs, seeking to express their personalities, overdo the informal. We believe one's endeavour should be directed, not to creating the garden of one's dream, but to confine one's self to trying to work with the natural setting and environment of your actual garden. Utilize the indigenous growth that can and does thrive where you live. By doing this, your work will blend in with the natural scenery which exists in the area. One cannot improve on nature, and, if one persists in trying to do so, one simply ends up with an artificial oasis."

Secateurs at the ready, you can now go forth and multiply relic boxwood cuttings to your heart's content. Think of the possibilities of playing around with past time in

your own garden today. Be sure to get permission (people do love to give away those cuttings) and remember to enjoy yourself!

Articles/links referred to in the text, all available on the web:Lodwick, L.A., Evergreen Plants In Roman Britain

Master Gardener Program, The Italian Garden

Salvesson, P.H. and Kanz, B., Boxwood cultivars in old gardens in Norway

Salvesson, Kanz and Moe, Historical Cultivars of Buxus sempervivens revealed in a Preserved 17th century Garden

American Boxwood Society newsletters http://www.boxwoodsociety.org/